If you want to make a writing instructor’s face purple, mention purple prose, the object of loathing for many professional writers, writing teachers, and readers. Purple is a lovely color, and yet it’s associated with a horrible writing sin. Why?

If you want to make a writing instructor’s face purple, mention purple prose, the object of loathing for many professional writers, writing teachers, and readers. Purple is a lovely color, and yet it’s associated with a horrible writing sin. Why?

What Is Purple Prose?

The term goes way back, originally being coined by the poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus (a.k.a. Horace) in Ars Poetica:

“Weighty openings and grand declarations often

Have one or two purple patches tacked on, that gleam

Far and wide, when Diana’s grove and her altar,

The winding stream hastening through lovely fields,

Or the river Rhine, or the rainbow’s being described.

There’s no place for them here. Perhaps you know how

To draw a cypress tree: so what, if you’ve been given

Money to paint a sailor plunging from a shipwreck

In despair? It started out as a wine-jar: then why,

As the wheel turns round does it end up a pitcher?

In short let it be what you wish, but whole and natural.”

(Here is an another translation from Latin to English.)

Because of its fundamentally poetic origins, it’s difficult to define purple prose, with many providing very vague definitions, but in general, it’s said to be superfluous, extravagant, showy, elaborate, and flowery language.

But who’s to say that language is “flowery” or “superfluous”? It’s very subjective by nature.

But who’s to say that language is “flowery” or “superfluous”? It’s very subjective by nature.

Other people might give a more helpful definition of purple prose: writing that calls attention to itself. When showiness outweighs meaning and communication and word choices are unnecessarily complex, objects are tersely symbolic, the appeal to emotion borders on the melodramatic, or the writer’s need to reveal their skills supplants what they’re trying to say, that’s purple prose. Examples of bad writing in general are littered with lavender phrases.

What Are Some Purple Prose Examples?

That last sentence could be a good example: “littered with lavender phrases” — did the showy alteration help you understand, or was I just showing off? It might not be entirely purple prose, but it lies in a gray area. (OK, I’ll stop with the color metaphors.)

Here’s another, more famous example of bad writing: We’ve mentioned it before in our blog post about writing opening sentences. (Poor Bulwer-Lytton gets so much criticism.)

“It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents — except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.”

— Edward George Bulwer-Lytton, “Paul Clifford”

This sentence draws attention to itself, describing the scenery with obvious language that’s meant to make something seem dramatic and threatening but doesn’t. It’s also overly descriptive and hard to understand. The author announces his unwelcome presence with a voice so insistent that it’s off-putting.

Certain genres, such as melodrama, romance, and teen romance, are famous for containing many works with flowery prose like this. In those cases, it’s both expected and occasionally enjoyed.

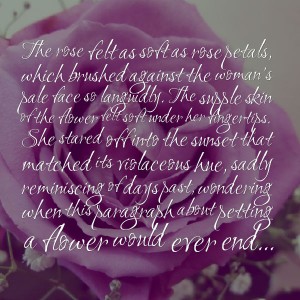

Here’s a fictionalized example:

Her eyelashes flickered in a fast movement along the tops of her cheeks to reveal pupils that took in bouncing light, revealing the sight of the man across from her.

Or you could just say “She glanced at him.” The underlying information is pretty much the same.

But Is That Bad?

We’ve all heard the argument against purple prose, even though we may not have realized it at the time: Omit needless words. Be concise. Get rid of unnecessary anything.

For most people, authors should behave as high-class waiters: You can infer that one exists, but you never actually see evidence of them. Your crumbs have been swept away. You have a champagne glass you didn’t have before. Surely, someone has put words here, spent hours and hours planning the plot, and agonized during revision. You wouldn’t know it, though, because all you have now is enjoyment. Bulwer-Lytton’s above sentence is like a waiter fumbling through the specials without introducing himself, forgetting to take your order, and walking away.

For most people, authors should behave as high-class waiters: You can infer that one exists, but you never actually see evidence of them. Your crumbs have been swept away. You have a champagne glass you didn’t have before. Surely, someone has put words here, spent hours and hours planning the plot, and agonized during revision. You wouldn’t know it, though, because all you have now is enjoyment. Bulwer-Lytton’s above sentence is like a waiter fumbling through the specials without introducing himself, forgetting to take your order, and walking away.

But sometimes, it’s OK to relate to the person behind the words and not just the words themselves. Some go so far as to suggest that there’s nothing inherently wrong with purple prose. It’s just a sign of inexperience, but when used purposefully, it can be a great deal of fun. In fact, we’ve rewarded past authors with flowery language, like Dickens and Faulkner, with years of fame; many of their works are deemed classics even today.

Should a Writer Avoid it?

When I was learning how to play an instrument, my instructor told me that I had to “play loud to play soft.” That is, I had to learn how to blast the brass instrument as intensely as I could to have the diaphragm strength to play softly and have the control I needed to do so well.

I didn’t take his advice, and I was a miserable trombone player.

So in a sense, a writer should feel at ease going as purple as possible in their first draft, as long as they’re absolutely relentless about killing their darlings later. A writer should be confident enough to create a monster of a sentence or a paragraph so filled with unnecessary tactile details that it feels like you’re there — or, if they need to, just ramble for a bit until they get to the next thought.

Blast away; don’t hold yourself back. But then, you have to rein it in, learn how to take those confident toots and blasts and make one smooth sound.

In other words, the answer is no and then yes. Write what you need to to get it on the page, and then attack your work with a red pen. Get rid of zombie nouns, bad, unhelpful prose, and over-elaborate explanations on the way to your final draft.

Hi there everyone, it’s my first pay a visit at this wweb site,

and paragraph iss truly fruitful designed for me,

kewep up posting succh articles.